Return To Book 3 Table Of Contents

Bits And Pieces… How Understanding The Small Things Can Make A Big Difference…

Truly these children had within them such a strong will “to understand” and “break the code” to the world about them, that in helping to have them achieve that, truly, we could make these children very, very productive members of society. Given the love of computers I had seen in Zachary, I had no doubt that children with autism, with their intense focus on details, and their need to figure out how things worked – their need to “complete the puzzle” - could become among the best computer programmers and engineers in the world. All they needed – was help – in breaking the code – in making those first “cracks” in the shell – “cracks” that - as in the case of an oyster – could reveal a magnificent and precious jewel within! Pearls could be created from a single grain of sand, and likewise, a single “crack”, that “first crack” in the shell, could allow for the eventual formation of a pearl in the child with autism – a child who also – was beginning with but the very basics!

As a grain of sand - became a pearl - so too could other jewels be found.

A lump of coal - so dark and difficult to peer through – over time, had the potential to become – a precious and sought after diamond!

So, too was this true of the child with autism – a child who so often needed only a little time, and a little “crack” in the shell! Too often, in looking at a grain of sand, a lump of coal, a child with autism, a person with mental illness – too often in looking at these we forgot that – within – there existed so much potential - simply waiting to be revealed.

There was no doubt that to produce a pearl or a diamond required a lot of time – and indeed – a lot of pressure – yet, although the days spent with a person suffering from autism, schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s could be very long at times, and full of so many pressures – emotional, physical, psychological, financial, social – I knew that within all that time – within all those pressures – there truly was the potential for the making and revelation of a very precious jewel.

In autism and certainly in Alzheimer’s, memories as they related to what so many of us considered our most precious gift of all – family – were simply “washed away” – like grains of sand swept under the sea by powerful and seemingly insurmountable waves or tides.

Zachary had certainly had his share of memory loss as it related to the concept of self. Yet, I had finally been able to bring him back in this regard. For now at least, he knew “who he was”. A great deal of that, I knew had been as the result of having provided him with “his label” – his reference from which to draw on. I had worked with him specifically in matters relating to the concept of self. That memory – and understanding of self – he had finally regained, although I very much knew that it could still be quite fragile. As to whether or not he had a “memory of self” or had simply come to create new memories of self based on the work we had done, I had no way of knowing for sure. All I knew – at this point – was that Zachary knew who he was. Indeed, I knew that many children with autism had come to once again have this same understanding.

History had shown that they these disorders, autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s, had common roots. Without an understanding of those common roots, however, it was unlikely that families of those with Alzheimer’s, for example, would be looking to see what those dealing with schizophrenia and/or autism were doing to help their loved ones. If disorders were seen as completely “unrelated” – a view I, personally, very much disagreed with – then, certainly, if the disorders were viewed as “unrelated”, their “treatment” or “therapy” options would be viewed as unrelated too! I was not sure that “treatment” was the proper word to use here since clearly, no one appeared to fully recover from these disorders. What I was simply trying to say was that if the disorders were seen as completely unrelated, then, the options available for dealing with these disorders would more than likely be viewed as unrelated also.

Yet, the parallels and the history – were there! There could be no denying that. But, likewise, differences among these disorders existed, too. There could be no denying that either. As I had done previously, I turned to what was known of brain structure, function and development for clues into why Alzheimer’s seemed to result in the total and complete loss of memory, whereas memory could be regained – or at least newly formed – in the child with autism. Indeed, everything I had seen in Zachary appeared to indicate he had not only regained the ability to form new memories but he had, undeniably, a fantastic ability to remember things.

Why the difference between autism – and Alzheimer’s? There was no denying that short term, long term and working memory had been known to be impaired in all three disorders – autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s – but why were issues of memory recall “so bad” in Alzheimer’s?

Work done by Dr. Fred Gage in the area of memory formation, specifically as it related to the hippocampus, seemed to indicate that the hippocampus regenerated new cells well into later years – perhaps to fifty or even seventy years of age. The olfactory bulb, according to Dr. Gage, was also known to produce new cells over time. Animal studies involving monkeys indicated that new cells in monkeys could regenerate over the animal’s lifetime.

Seeing that “memory functions” existed in several parts of the brain provided hope in that perhaps memory functions in a less impacted area could be drawn on to form memories relating to “something else”. For example, perhaps via motor functions and “repetitive tasks or therapies” (frontal lobe functions) memories could somehow be formed relating to what would normally be considered “non-repetitive or motor” things – things that would not normally be learned via repetition or “leaned motor skills”. As I suspected that the sense of smell could be used to help with issues of the concept of self, I also suspected that motor functions or “learned tasks” could be used to help with issues of memory. In other words, if one area was not working properly, try to draw on another by using as many of those things or functions “available” in that “other area” because co-located functions within the brain were much more “inter-related” than we may have ever imagined.

The hippocampus had long been known to be associated with memory formation. It was believed that damage to this area prevented one from making “new memories”. Short and long term memory acquisition appeared to reside in the temporal lobe and memory as it related to learned motor skills resided in the frontal lobe.

The hippocampus… how was it that an area of the brain that should be developing cells throughout life – was actually losing them? This, again, very much paralleled what we were seeing in schizophrenia. In schizophrenia, during puberty and through the early twenties, during a time when gray matter should be further developing and thickening – the person with schizophrenia was actually losing gray matter. What was going on? In both cases, Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia – new cells should be developing – yet they were being lost! Why?

The only explanation I could come up with was that, in my opinion this had to involve mercury because mercury appeared to target developing or immature cells the most!

Well, given that Dr. Fred Gage had shown that the hippocampus continued to develop cells late into life, these in my opinion, would be the most susceptible – and “coincidently” – the hippocampus was that area - “most hit” - in Alzheimer’s!

In Alzheimer’s, the cerebellum had already had the chance to fully reach maturity. That, clearly was not the case in autism – where the cerebellum was that part of the brain that appeared to be “most hit” – that part of the brain I very much suspected to be “the brains of the brains”. Persons with schizophrenia were “in the middle” of the spectrum. There cerebellum had been given the opportunity to mature somewhat, but, for persons with schizophrenia, those parts of the brain developing the most – the most immature cells – would be those involved in that gray matter thickening wave that started at the onset of puberty and lasted until about age twenty. Thus, it made perfect sense that given gray matter was thickening throughout the brain, and “immature cells” were found throughout, that the entire brain could potentially “be hit” at puberty by mercury!

In the child with autism or the person with schizophrenia, memory appeared to be “less impacted” than in Alzheimer’s. I now very much suspected that this was due to the fact that in infants and young children and in adolescents and young adults, there were “more immature cells” – the cerebellum, the corpus callosum, the gray matter thickening process – and hence, the more immature the cells, the greater the target. Certainly, that seemed to be very true and in my opinion, was exactly what we were seeing reflected in these disorders – autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s – truly, in my opinion – just shades of the same thing!

In my opinion, iron overload and nitric oxide could still also very much play a role in all this, but, the case for mercury, as it related to damage in developing cells especially, certainly appeared quite strong!

Before leaving the subject of “memory formation”, I wanted to share a few thought on what I had seen in my own son… bits and pieces to my puzzle that would perhaps be of help to others.

In so much of what I had come to understand in Zachary, there could be no denying of the critical role of “that label” or “that reference” for him to draw on an the need to show Zachary “more options” or “more ways” to look at things as he formed new memories. The key, in my opinion, truly was in making him see that, for example, there was more than one “reference” for adding numbers for example.

I selected these particular examples because they involved short term, long term and working memory. These were but a couple of examples, but the concept was the same whether one was working with numbers, language or something else. It was also important to keep in mind my belief that the various parts of the brain were perhaps much more inter-related than we may have ever imagined.

Let us take first the simple concept of teaching basic addition. Teaching basic addition obviously involved the working memory, short-term and long-term memory. This also involved functions such as “categorization” and “auditory processing” in the temporal lobe and “higher functioning” in the frontal lobe. Although visual processing was usually involved, clearly, a blind person could learn math too.

If you considered how math was usually taught, it was normally something like this:

1+1 = 2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4, and so on.

In other words, the “peg” or “constant” was the number “1” and what changed were the “other numbers”. It soon became evident to me that in working with Zachary, a child with autism, a child who very much lived “via reference”, there was an inherent problem in this approach. If I taught Zachary math in this way, I was teaching him “a reference” – that 1+1 = 2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4 and so on. Although this was true, I was in actuality, only providing a partial reference for Zachary. Given I knew his was a world of “reference living”, I personally, saw a huge problem with this. I was only providing one of many possibilities for the sum of “2”, or the sum of “3” or the sum of “4” and so on and not showing that – potentially – there were many other ways to come up with the same answer. Indeed, there were many other possibilities… and they increased tremendously the “bigger” the number for the sum.

As such, in teaching Zachary, I decided to “peg” the answer. In other words, I did the following for numbers 1 through 18 (because to do basic math, Zachary had to be able to add at least up to 9+9 to get to the stage of graduating to counting involving units of “ten”). In “pegging” the answer, I now provided for Zachary an understanding that there were “many ways” to get to a specific number, “many options” available for doing the same thing. For example, to get the number 18, you could do:

|

18 |

+ |

0 |

= |

18 |

|

17 |

+ |

1 |

= |

18 |

|

16 |

+ |

2 |

= |

18 |

|

15 |

+ |

3 |

= |

18 |

|

14 |

+ |

4 |

= |

18 |

|

13 |

+ |

5 |

= |

18 |

|

12 |

+ |

6 |

= |

18 |

|

11 |

+ |

7 |

= |

18 |

|

10 |

+ |

8 |

= |

18 |

|

9 |

+ |

9 |

= |

18 |

|

8 |

+ |

10 |

= |

18 |

|

7 |

+ |

11 |

= |

18 |

|

6 |

+ |

12 |

= |

18 |

|

5 |

+ |

13 |

= |

18 |

|

4 |

+ |

14 |

= |

18 |

|

3 |

+ |

15 |

= |

18 |

|

2 |

+ |

16 |

= |

18 |

|

1 |

+ |

17 |

= |

18 |

|

0 |

+ |

18 |

= |

18 |

For Zachary, this did several things. It showed him first and foremost that there was “more than one way” to do the same thing and it provided for him the references he needed to draw from. Granted, you could never provide “all references” in “all situations”, but, by using math, I could provide the “concept” that there were “more possibilities” to something than “just one” – in anything… be that math, language, behaviors, routines, etc. This concept, in my opinion – the concept of showing “more ways”, “more options”, was key in getting children with autism away from their “inflexibility” in so many issues.

But, this simple concept also provided much more for Zachary. It provided for him “the pattern” to see how things worked and hence, the ability to understand how to “break the code”. Zachary easily picked up the concept that on one side, the number went down by one - on the other, it increased by one. Thus, he could actually “see” how this worked.

But, there was still more… for Zachary, this still provided a basic reference… a starting point that he could associate with – a reference easily retrieved and drawn upon or enhanced from there. The obvious “key reference” – though not the only reference for “18” – was the middle point – the fact that 9+9 = 18. For children who loved that concept of “sameness”, this particular reference was key. From this reference point, Zachary could then in his head come to learn to “move up or down” in the chart.

In my opinion, it was also necessary to focus on providing what I came to call “primary pegs” – those basic reference points – the starting points – that could then be used as “key references” in charts such as the “18” chart provided above. Primary pegs – in basic addition – would include the following:

|

Primary Pegs |

||||

|

0 |

+ |

0 |

= |

0 |

|

1 |

+ |

1 |

= |

2 |

|

2 |

+ |

2 |

= |

4 |

|

3 |

+ |

3 |

= |

6 |

|

4 |

+ |

4 |

= |

8 |

|

5 |

+ |

5 |

= |

10 |

|

6 |

+ |

6 |

= |

12 |

|

7 |

+ |

7 |

= |

14 |

|

8 |

+ |

8 |

= |

16 |

|

9 |

+ |

9 |

= |

18 |

|

10 |

+ |

10 |

= |

20 |

These “same numbers” being “added together”, were in my opinion, key in the life of a child who loved “sameness” and as such, could very much be used to one’s advantage in teaching math based on a “peg system”.

But, there was still more… for Zachary, this also provided that key “categorization” that was so necessary to the understanding of math, language and so many other things in life. A chart such as this provided for “inherently correct” places for things. That was good – initially – but in my opinion – this was but a first step. Eventually, I could easily go to “moving them around” though… thereby, once again, increasing flexibility. For example, although the answer remained the same, I could now change the way “things appeared” in the chart. I could select a “random order” for all the ways to “make 18”, I could show addition involving “even numbers” first, then “odd numbers”. There were truly many things one could do to show that one answer could be achieved in many, many ways. The beauty of this was that it also prepared Zachary for the eventual learning of “negatives” being added into the chart. For example, I could show the fact that [–2+20 = 18] and so on. I could simply add in the “negatives” later on to further build on the concept - in this case - of math – although the application of this same concept could be done for many, many situations relating to many, many other issues.

I also taught Zachary the 1+1 =2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4 and so on method, but, my primary focus, initially, was on my “peg system” whereby the “peg” was - the answer – not a “variable” within an equation! Providing the “normal method” allowed Zachary to then see how “pegging” different parts of the equation changed the answer! In everything, I tried to provide for Zachary different “ways of looking at things” – “more ways than one” way!

Teaching Zachary math in this way certainly involved his working memory… and it made that “working memory” work in a “flexible way” – because now – he truly saw there could be – more than one way – and I could then apply that concept to much more than “just math”. I could “carry this lesson” to all aspects of life!

As I worked with Zachary, so many things became evident to me. The simple fact was that whether or not a child had autism, all children - all persons - pretty well had the “same brain” – overall. Functions within the brain were all located “in the same place” regardless of whether or not one was “normal” or suffered from autism, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s or any other disorder. A “disorder” in the brain resulted in just that – “dis – order” and the key was in providing once again for something that made sense – in breaking the code to how to once again – provide “order” so that things could once again be understood. As such, these methods could be used for teaching – all persons.

The difference in these methods for teaching math had shown me a great deal more in terms of “order” as it related to memory. There was no denying that in Zachary, there certainly were issues with short-term memory. I could attempt to teach him a concept over and over and he would fail to remember something he had just uttered. Again, the best example of this had to do with my teaching Zachary “basic addition” – not with the “peg” system, but the concept of teaching math via flashcards that were to be memorized and were provided in completely random order. In such a system, again, the answer would, by definition, not be “pegged”. This was the “normal math” – flashcard memorization – with a twist. I knew Zachary needed to be able to go through flashcards – randomly – and provide the answer and as such, although I very much focused on the “peg” system at first, I also worked with the “normal” system, too, of providing “randoms” in memorization exercises.

Since I knew that Zachary lived “via reference”, I now work at providing "as complete a reference" as possible for him via random flashcards. But, these too, had to be modified from what you could normally buy in the store.

To teach Zachary addition via flashcards for the number 0+0= 0 through 9+9 = 18, I would not use flash cards that simply showed the question without providing the answer. Most flashcards in a store would simply provided, for example, 9+ 9 on one side and the child would be expected to simply memorize the answer – but the answer was not provided since those cards in the store were just “for practice”. For a child with autism, in my opinion, that was not the way to go. In my opinion, these cards failed to provide that “critical second side” to each card – “the twist” - the “opposite side” of each card had to provide the 9+9 along with the answer to the question “= 18”. Thus, in my system, one side of the card only showed 9 + 9 and the other side showed 9+9 = 18.

In working with Zachary, if I saw any hesitation at all, I did not wait for him to “guess” the answer, I showed it to him. Guessing allowed for the opportunity to form “inaccurate memories” or “inaccurate references” and as such, I wanted to keep those to a minimum and when Zachary did guess, I was sure to immediately show him the proper “reference” or answer by simply “flipping” the card over for him to see it as I called it out. That provided a “visual” as well as the “auditory” reinforcement to build that association for the particular math flashcard we were working on.

Children with autism should not be expected to "guess" or come up with the answer on their own – at least not initially. In my opinion, they had to first be provided with the answer or correct reference as much as possible and then be expected to learn it and commit it to memory. The same would be true of “math concepts” – or in my opinion, so many other areas of life. Several critical examples had to first be given in order to teach the concept – and then “practice” exercises could be provided. In looking at so many teaching materials, clearly, they failed miserably in teaching “the concepts”. Time and money were but two examples of this – as such – again I created “my own tools” for Zachary in these areas and made these available on my website under I section called “Teaching Tools For Parents”.

I had spent a great deal of time in coming up with my “time and money” series of materials. I had only needed to introduce the “concepts” once or twice – and as such, although this appeared “rather extensive” compared to what schools provided – the simple fact was that these materials taught “the concepts” and as such, Zachary easily picked up on “how things worked” and at age five could already tell time – using “to, after, and quarters” also – and was already beginning to count money quite well after only a few hours on the subject of money. “Time” had already been mastered. With so many things, I always found it took me much longer to “come up with the tools” than it did for Zachary to grasp the concepts and as “extensive” as the tools appeared, if done properly, the concepts were mastered rather quickly. I figured I had spent about three weeks coming up/making my “time” materials alone. In my opinion, I could either spend the time making the tools my son needed to help him master the concepts quickly, in spite of how long and how much time it took me to do this… or I could work with “incomplete” materials and have him struggle with the concept for a much longer time. Zachary certainly did not need confusion in his life in the form of inaccurate or incomplete concepts and as such, I found making my own materials had really paid off in terms of helping him understand concepts much more clearly and much more quickly.

As I went through so many teaching materials, there was simply no denying that today – materials provided to teachers in classrooms – simply failed to teach “basic concepts” – having huge “gaps” in so much of what was provided – and expecting teachers to do all the “filling in”. Today, that was simply impossible to do given the tremendous base of knowledge that existed. Teachers were not the root of our problems when it came to failing school systems – the root of the problem was in poor and hence confusing teaching materials! I will cover more on this particular issue in my fourth book – a book on language and communication that will also provide many “tips” for teaching children with autism!

In my opinion, that “first reference” was critical and as such, it had to be as accurate and complete as possible – and it was the “complete as possible” that had prompted me to use my “peg” system first and foremost!

There was no doubt in my mind, that in a child with autism, that “first reference” even if “inaccurate” could be “engrained” in the brain and committed to memory – just as easily as an accurate reference and hence, it was critical to always correct Zachary’s inaccurate guesses or inaccurate utterances during the day… his “inaccurate anything”. An inaccurate point of reference once burned into memory, in these children would be harder to correct at a later date because memories had a way of becoming “more solid” over time – even “inaccurate memories” or “inaccurate labels” (as I discussed in greater detail in my second book – Breaking The Code To Remove The Shackles Of Autism: When The Parts Are Not Understood And The Whole Is Lost!). In my opinion, it would take a great deal more work to “change a bad reference” in Zachary than it would in a “normal person” – and as such, I worked very hard at providing as accurate yet flexible a “first reference” as possible in teaching my son.

Note again, that this “method” spanned far beyond “book learning”. First references also had to be accurate in terms of, for example, “acceptable behavior”. It was easy with a child with autism to “let them get away with things” – like perhaps hitting a sibling. That was one of the worst things a parent could do – to allow a child to have a “reference” that this was an “ok” thing to do. Pitying your child did more damage than good – understanding and patience were absolutely key – of that I had no doubt – but, pity of a child with autism – to the detriment of another child – in my opinion was unacceptable – because given these children lived “via reference” – ultimately – such “references” would be to the detriment of the child with autism also. Explanations of appropriate behavior were thus key!

Zachary had been taught very early on that “hitting his sister” was not acceptable behavior. As such – at least for now – he was a very gentle child. Although I did not know what was ahead in terms of “puberty onset” (given temporal lobe damage could result in things like increased aggression), all I could do was take things one day at a time – and keep what I had learned throughout this journey with autism always in the back of my mind as things related to “appropriate references” for Zachary. Very key was that the parent’s behavior also provided “a reference” and as such, parents had to be very, very cautious of what they were teaching their children in any “discipline” behaviors/reactions. Violence in these children especially, would only promote the use of violence if this was “taught” as “acceptable” As such, I was now very, very careful of the message given to my child via discipline methods.

Thus, I very much tried to give Zachary accurate references to draw from and to teach him flexibility in arriving at answers and the best way to do that was to teach him by “providing the answers" he needed to have for that first initial "accurate reference"… in math… and in life!

So, I went to the store and for .50 cents per pack, purchased four packs of blank cards to make my own flashcards for Zachary. I took different color markers for each set... for example 0+0=0 through 0+9=9 was in one color, 1+0=1 through 1+9=10 was in another color and so on. When I wrote these out, I did not write them horizontally (as shown here), but rather vertically (as you would do if you were adding large numbers together). That way, as I progressed with Zachary in math, the concept of number alignment would have been there from the start and that would help with the "carry the one" type addition and so forth later on. Later, I then provided the “horizontal” equation on a chalkboard to show Zachary you could also write the same equation in different ways (horizontally or vertically).

Thus, in teaching Zachary addition, I had a full set of flashcards – from 0+0 to 9+9 with one side having the answer, and the other - not having it.

So, a completed card would have for example, 5+4 = 9 on one side and on the back side, it would have 5+4 with the line drawn below both numbers to indicate "equal", but on the back side, the answer would not be provided. By putting that “equal” line on the side with no answer, I was providing for Zachary the “prompt” that something “went below” the line – the answer I needed him to provide. That “line”, in and of itself, became a reference acting as a “prompt” for an answer.

Once I had my cards done, the exercises started. I first showed Zachary the 5+4=9 card – the side with the answer was shown first to provide “the reference”. I then asked him repeat it once. I then turned the card over and ask him the very same question... only without the answer shown. Usually, he could easily remember what he had just seen on the other side and give me the right answer although there were clearly times when he had difficulty doing even just that. Yet, if I showed him the 5+4 = 9 card and then said, "ok, now close your eyes and say it", then, he would have much more difficulty... some he would get, others he would greatly struggle with. Those he would get were the "easier" additions and a few of the new ones.

Understandably, he had more trouble with the "bigger numbers" he had less exposure to them initially. Recently, however, I noticed that Zachary was very much using our “peg” system and that he could now add almost all basic numbers from 0+0 all the way to 9+9. Actually, because he had figured out the “pattern”, I could now add to the “pegs” and do, 11+11 or 12+12 and he could get the answer. He knew 10+10 = 20 and he would just work from there.

Given that “pegs” were provided, that made learning the “in between” numbers much easier too. For example, since 10+10=20, it was easy for Zachary to understand that 10+11= 21. As such, Zachary could use his “primary pegs” to get to the “in between” numbers.

Zachary, from the very start, had shown great enthusiasm in going through the cards and my “peg” system.

As we had worked with flashcards, there really was no stress there because if he did not remember, I just turned the card over again, showed him the answer and he simply proceeded to repeat verbally the addition with the answer. Then I again turned the card over and had him say it without seeing the answer.

Although now, Zachary was much better with his math than he had been at first, there had been valuable lessons in those first few days of working on math with flashcards – lessons I wanted to share with parents.

What became very, very clear to me in working with “flashcards” was that when I asked Zachary to "close his eyes and say it", I could truly see just how impacted his short term memory really was! "Out of sight out of mind" was certainly evident – even though he had just seen the card less than two seconds ago. Note that I had briefly tried “flashcards” before coming up with my “peg system” and it had been at that time that I realized the old way of doing things – “flashcards” alone – was simply not working for Zachary… and hence, I went to my “pegs”.

Early on though, when I had worked with flashcards only, again, I made sure I minimized the stress on Zachary. When I said, "now close your eyes and say it", he knew that he could always just open his eyes and have the answer there if he needed it... and often, he did. So, to go through a card like 6+7=13 for example, when I said "now close your eyes and say it", Zachary would close his eyes and say one number... usually he said the first one (here 6) but then forgot what came next so he opened his eyes to see the next number (in this case 7). He would then close his eyes and repeat 6+7 = and then he would "blank out again" and open his eyes once more to see the answer. Once he read it off the card, he would close his eyes again and say 6+7=13. I would then reinforce by flipping the card over again and having him say it without being able to see the answer... and then, I moved on to the next card.

In doing this, there were also times when I noticed that when I said, "ok, now close your eyes and say it" that Zachary would start off with the wrong "second number" and catch himself and want to start over... for example, if the card was 6+7=13, when I said "close your eyes and say it", he could say 7+ and then he would realize "the order was off" and he would stop and open his eyes to get the first number first...in this case 6 before going on. So, he clearly had enough short-term memory to recall the "order" of things and knew when something was "wrong". That was evident – and a critical piece to the puzzle – at least in my opinion!

Thus, short-term memory was impacted in certain ways, but not others - the "order of things" seemed to be properly recalled. Given that I knew Zachary lived “by reference”, this now made sense to me. That was very, very interesting indeed. I knew that “categorization” and “memory” functions as they related to short term and long term memory formation/acquisition were co-located in the temporal lobe. Zachary had remembered – the order!

This only further solidified my belief that functions co-located within a particular part of the brain were much more inter-related than we had perhaps ever believed. As such, one should be able to enhance certain functions by drawing on “other functions” co-located in that part of the brain.

Although I was only starting on the concept of “carry the number” in basic addition, note that I would not use the phrase “carry the one” with a child who had autism – that would be an “inaccurate reference” because the number carried could obviously be a 2, a 3 or other number larger than 1. To state “carry the 1” would solidify an “inaccurate reference”. As such, this operation, when I arrived to it, I would refer to as “carry the number” – thereby providing a reference that “the number” could change – it did not have to be a “ 1” and could certainly be – something else – something other than 1 (i.e., when many numbers were added together). Having spent just one hour or so on this subject so far, I already saw that Zachary was “resisting” the idea of “splitting numbers” when math additions required “carry the number” type stuff – and necessitated a number be placed in the “tens” column and one below “the line”.

For example: 15

+16

2 1

I found that if I made up terms like “a split number” to show that the 1 in the answer went with the “little” 1 next to the five to make 11, the sum of 5+6, that this helped Zachary deal with the “splitting of numbers”. I also used “boxes” to fill in to provide that “complete the puzzle” concept when it came to issues like this. But, again – the point here was not to state “carry the one”, but rather to state “carry the number”… or in this case… “carry the split number”.

The lesson in all this was that in teaching Zachary math using flashcards had remembered – “the order”… and that was the key to now teaching him – so much!

Although the math example was a good one, there was yet, a much, much better one.

If indeed memory acquisition were co-located with categorization and the “understanding of language”, would that mean that the “understanding of language” could be enhanced via categorization methods? Would memory as it related to the learning of “language skills” be greatly enhanced via categorization functions?

On so many occasions, I had tried to get Zachary to repeat a sentence. He had time and time again been able to recall the first few words he had heard, but, then, usually failed miserably in recalling the rest of the sentence. Anything that involved more than two or three words to repeat had always been a major task for him. In my second book, Breaking The Code To Remove The Shackles Of Autism: When The Parts Are Not Understood And The Whole Is Lost!, I had given examples of what I was now just starting to do to teach Zachary language skills.

Although I had discussed this somewhat in my second book, I had now come to understand so much more when it came to communication and language with my son who had autism that immediately upon completion of this text, I would write a fourth book – dealing specifically with language issues. I did, however, want to touch on this subject here as it very much related to matters involving “memory” also.

If my theory were correct, then, “categorizing language” would be key to helping Zachary understand and memorize certain language rules. But, how did one go about “categorizing language”… “categorizing speech”… “categorizing a sentence” in a way that could be understood by a five year old child?

While I was in fourth grade, I had been taught grammar using a concept called “bubble graphs”. Although I would have to modify this concept to better meet Zachary’s needs, within it was the foundation I needed to “categorize language”.

Although I would only briefly touch on this subject of “language categorization” or “language compartmentalization” here, I went into this in greater detail in my second book and since that section was rather large - I would not be replicating it here. This second book was posted in full on my website, www.autimhelpforyou.com. Also, I would discuss matters relating to language and communication specifically, in much greater detail in my fourth book – my “next project”. :o)

I did want to provide a quick example of something I had done with Zachary – simply to show the concept and show how this truly, did appear to work.

Again, Zachary had always had great difficulty in remembering more than a few words to be repeated. As such, I started with a simple sentence and built upon it so that I had three sentences to work with.

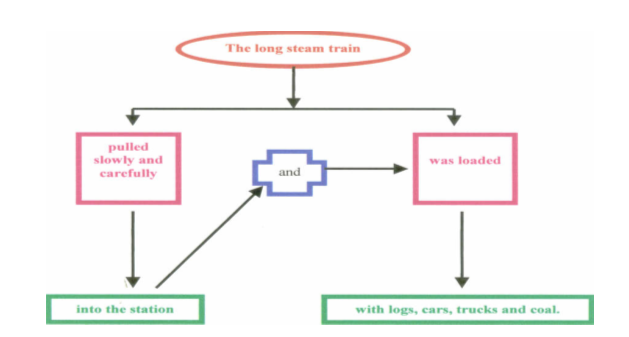

1. The train pulled into the station.

2. The long train pulled slowly into the station and was loaded.

3. The long steam train pulled slowly and carefully into the station and was loaded with logs, cars, trucks and coal.

Needless to say, the third challenge, for Zachary, should have proved to be a rather huge challenge given he could barely repeat more than two or three words. All three sentences had been introduced to Zachary within a matter of a half hour. I proceeded to “draw” each sentence in a very specific manner for Zachary… adding more with each sentence.

Below was a reproduction of one of two drawings for sentence three.

Zachary, a child who had been unable to remember more than a word or two, had, with the help of this graph, been able to remember the entire sentence – in perfect order within a matter of a few minutes! He then remembered it the next day… the next month… and two months later.

I had not asked Zachary for this sentence in quite a while – over six months. When I showed him the graph of this sentence as I typed this text, I asked him to repeat the sentence. He read it twice on the monitor. I then asked him to tell me the sentence without looking. Amazingly, he could recall it – again – in perfect order – within a matter of just under a minute. Months later, he had obviously remembered this sentence! Thus, from what I had seen in my son, working memory, short term memory and long term memory all appeared to work better in matters of “recall” when language involved “categorization”. Graphs were key to first teaching language. As sentence structures changed, one could then “change the graph” to show again that there were “more ways” than one – of saying the same thing. One could then “change the words” to show how the meaning of things could change based on the words used, etc. These were all issues I would address in greater detail in my fourth book.

My intent here was simply to show, that as I had suspected, working memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory as they related to the understanding of language and the recall of language worked best when language was “categorized”. Originally, I had thought that the visual perception in the temporal lobe may also be helping in this issue, but I later came to understand that visual perception in the temporal lobe really seemed to be only for the recognition of faces, body parts and places. So, it had to be the “categorization” and “understanding of language” that were key – although this approach certainly had the capability of drawing on many other functions in the brain as well.

Clearly, the “understanding of language” and memorization of language concepts could perhaps be best achieved when language was “categorized”. Note that understanding of language, memory acquisition and categorization were all in the temporal lobe. I could then “bridge over” to the other parts of the brain also by using this method. As I drew the parts to the sentence, I was using motor skills – and engaged Zachary in the “actual drawing” of the sentence, as I called out the parts. For example, I said: “subject info goes here – The long steam train” - as I drew the oval with him and wrote in the words.

This therefore, involved motion and word associations along with higher thought processing and the production of language (since he often repeated what I said) – all frontal lobe functions. In addition, parietal lobe functions were involved – spatial processing, visual attention, touch perception (holding the chalk, erasing mistakes, etc.), manipulation of objects (the chalk, eraser, moving of sentence parts around), goal directed movement (filling in the parts), and the integration of sensory input into one concept (seeing how all this made – one sentence). Three-dimension processing – also a parietal lobe function – in my opinion could perhaps better be achieved via a computer than a chalkboard. Finally, the occipital lobe was also very activated as we did this.

Thus, teaching language could best be done via such methods – and ideally – on the computer – and hence, my strong belief that we needed software specifically designed with the child with autism in mind – although, clearly, such methods could work for all children and hence, alleviate many “integration” issues in schools – because – after all – all children did have the same basic brain structure and function and if this method worked well for children with autism, I had no doubt it would work well for all children!

Amazingly, I found I could also simply “use my finger” in the air as I spoke and pretended to point to graph parts in order to take the graph “off the chalkboard” and the visual realm of language and more into the realm of understanding language based simply on the “hearing” of language. Although I had not spent a great deal of time on this, I knew this would be the key to getting much more conversation in Zachary and a greater understanding of language still. The concept or key idea in my opinion, would simply be to have Zachary get to a point where “graphs” were no longer needed because the graph could simply be made within his “internal computer” – his brain – as the conversation happened. My goal was simply to help him “understand” how the “pieces fit together” – to help him break the code – to language! Once he understood how the pieces fit together, I had no doubt that he could move forward quickly in the area of conversation.

Although I had not spent a great deal of time with Zachary on “grammar” or sentence structure issues given he was only five years old, I knew that this was definitely an area to tackle in the next year or so. Yet, the short time I had spent on this method had clearly shown me that this was a powerful and effective way to teach Zachary language. Again, he had remembered “the order” so perfectly. I now had to focus more on teaching “the concept” by now defining for him all the parts that “made up a sentence” and then, “putting it all together” as I had done in this example. I knew I had jumped ahead of myself and now had to backtrack to explain the various parts and how they all fit together – and hence, my primary motivation for book 4 – dealing specifically with issues of language and communication and providing more in terms of how to teach children with autism.

As I wrote my second and third (this one) books, something had become very obvious to me – in trying to help others by providing “experiences from our journey” for other families dealing with autism, I had found that my knowledge in so many areas was greatly enhanced – as I wrote and shared experiences. As I recalled what we had been through – I came to better understand it. As I looked to understand the science, I was forced to research more and more – often – while also writing – and so, although it took a great deal of energy to provide “our experiences”, it had been in doing so that I had come to understand so much more – myself! It was as a result of this that – I, too – had been forced to look at things in “more ways”.

Thus, the key to so much in helping the child with autism was to simply look at things in “more ways” and in using as many parts of the brain - at once!

More ways… more options… different ways for showing… the same thing!

This fourth book, would have implications that spanned far beyond “just trying to get children to speak”… and as such, I encouraged all families to read this book once completed also.

With language, I would simply show that “different ways” of saying something gave you “different results”. As with everything, it was in my opinion, key to provide an initial reference of “how things worked” and then build on that to provide for the “flexibility”.

In working with these issues as they related to math, language and memory, I found Zachary would easily "catch on" to the pattern and/or concept and be able to give me the answer when I reproduced this on a chalkboard and left out a number in the equation or words in the bubble graph. I would then have Zachary read off the entire equation for each line, or the entire sentence, and then, I would say, "ok, now, put it in your head".

When I said that, Zachary would put his hands on top of his head and repeat what he had been just taught. Then, I'd say, "ok, now do it with your eyes closed" and have him repeat it one final, third time. In my opinion, this helped with issues in "working memory". Each time we did these exercises, they seemed to get easier for Zachary. When he was "reluctant" to do the work, I just picked a really "easy peg number" or sentence for that day or something that was of special interest to him (i.e., using examples involving trucks, etc.)

If categorizations helped memory acquisition and the understanding of language, I suspected categorization could also be used to help with memories as they related to face and voice recognitions – also temporal lobe functions. In my opinion, this would take more than simply labeling a person as “your brother” or “your sister”, this would require providing an understanding of the “family unit concept” first and how the person suffering from autism or Alzheimer’s fit into that “family unit”.

The key was to activate the working memory, short-term memory and long-term memory and to have the concepts later made applicable to as many other “life situations” as possible. In everything the key to “building memories” had to involve the use of “categorizations” and “pegs” or “references” that could then be expanded.

The critical variable of “order” was key to dealing with so much of what we saw in these “dis-orders”!

The beautiful thing in all this was that given we all had the same basic brain structure and function, tools that worked for children with autism should work for any child – and as such, this could help with integration issues within school systems!

I personally had been taught grammar using bubble graphs – a concept I had remembered decades later although I had greatly modified what I had been taught and geared it specifically to autism. I saw no reason why teaching of grammar and language could not return to this concept within the school system – especially if it could be done via software! This, in my view, was a fantastic and fun way to teach grammar and a great way to help children with autism – indeed all children – to learn language skills and commit critical concepts to memory. I had no doubt that for many, many children with autism issues with working memory short-term and long-term memory could be helped by such methods.

Needless to say, given I personally was not a programmer, I certainly had great interest in seeing teams put together to put these concepts into application and the development of software for children with autism or other persons with the need to learn or “re-learn” language skills. I encouraged persons willing to donate money and/or time to such projects to contact me via my website. In my opinion, there was no doubt that this could literally help millions of people worldwide and as such, I certainly hoped those in government would see value in spending significant funds for such projects also. Many families certainly felt that government agencies had contributed to this social catastrophe so many of us now knew as “autism” or “Alzheimer’s”. It was time the government finally helped be part of the solution instead of fighting families that had been so devastated by these disorders.

Although I personally could not “code software”, I had for close to ten years worked with programmers at Ameritech – instructing them as to “what I needed” and then working at software testing and training for a rather large sales force. As such, I had a very good idea of what was involved. This would require a lot of people and a lot of money for software development, hardware, and for putting the right teams in place to work these many areas of “teaching”.

We, as taxpayers, had spent billions on research – much of it, quite frankly, doing very little to actually help those so impacted by autism. It was now time to spend some of those billions of the victims of these disorders – on therapy and special programs. Only taxpayers could force this change and as such mental illness and the many issues discussed in this text had to be made an election issue – in all future elections. Our children and loved ones no longer had “time to waste”. The clock was ticking – I knew that – and many others now knew that as well. With so many of us heading for Alzheimer’s, I think all of us had a very special interest in seeing these things accomplished.