Updates To Language Section Provided In Book 2

In going through this section, at least initially, I suggested readers “go back” to the three-page,

basic, brain structure and function overview often to better understand the issues. See the Table of Contents for the page number and “keep a finger on those pages” as a place marker as you go through this section. For a person who had not read some of my previous works, this section could seem a little overwhelming if not read with the help of that basic overview. However, when the overview was kept as a “reference”, the issues, in my opinion, became clear rather quickly and were much, much more easily understood – especially when the University of Calgary video on neurodegerenation was also kept in mind – a video that clearly showed how mercury completely devastated neurons and shrank them to approximately half their original size. Again, this video, for those who had not viewed it, was available on my website and I encouraged all parents to view this information.

The video on neural degeneration could take quite some time to load, but I urged you to take the time to allow it to load. A picture in this case was worth more than a thousand words – truly, it would leave you speechless – and I suspected that this video showed exactly why, so many children with autism – indeed – now lived – speechless!

As I now looked back and tried to remember “what had worked” for Zachary in terms of language development, and looked at that from a brain structure and function perspective, there definitely were some things that had been absolutely key – things that were now so much better understood when looked at from this brain structure and function perspective.

I did want to remind readers that the first thing we had done was to place Zachary on a casein free, gluten free diet. For him, that had made a huge difference. I knew that for some parents, the change in their children did not appear “that great” when their children were placed on cfgf diets and as such, many appeared to give up after a few months. Given it took gluten close to ten or eleven months to leave the body, we had decided to stick with it, and I was glad we had. Indeed, it had taken close to a year for Zachary to finally put together two or more words. I now understood why that was (more on that later). Zachary was fantastic as “labeling things”, but, conversation, had simply not been there and that first year had seemed so, so difficult as a result of that. In looking at language development, however, there appeared to be no doubt that even though some children with autism were on cfgf diets and others were not, there were still certain “common themes” to language development for those children with autism who did develop language. Perhaps the most common of these “themes” was that behavior known as “echolalia” or the repeating of words said by someone else.

Echolalia was defined as follows - I quote:

“ECHOLALIA is a meaningless, persistent, verbal repetition of words or sounds heard by the patient - often with a mocking, mumbling, staccato, or parrot-like tone. Echolalia is in response to the same stimulus, whereas perseveration is repeated responses to varied stimuli.” [end of quote, emphasis added, Jacob Driesen, Neuropsychology and Medical Psychology Resources, Glossary, http://www.driesen.com/glossary_e-i.htm].

Meaningless! Every time I read that word as it related to echolalia, I could not help but laugh. Perhaps “the experts” did not understand this parroting, but that, in my opinion, certainly did not mean this language was necessarily “meaningless chatter”.

Why was it that children with autism so clearly engaged in this “parroting” behavior when it came to language? They pretty well seemed to do this universally. Indeed, it seemed “rare” to find a child with autism that did not engage in this parroting form of language. That in and of itself told me there had to be “something” to echolalia – it had to serve some kind of “purpose” in these children.

For decades we had viewed this behavior as “dysfunctional”. Now, as I looked at this “parroting” from a brain structure and function perspective and thought about language development in Zachary - it made perfect sense! This form of language, in my opinion, was anything but “meaningless”.

Functions in the temporal lobe included, among others, the following: auditory processing, memory acquisition, understanding of language, voice and face recognition, categorization of objects, some visual perception, ability to distinguish between truth and a lie. All of these had implications in the behavior known as “echolalia”.

Of these functions, clearly the obvious one relating to language was that of “understanding of language”. But these “other functions” listed above, also very much played into language development – in not only a child with autism – but, in any child.

Let us remember my three major premises: 1) there appeared to exist little or no communication among the various parts of the brain in children with autism, 2) those functions co-located within a specific part of the brain (i.e., the temporal lobe) appeared to have “magnified communication” in children with autism, and 3) it appeared those functions that were co-located within a specific region could be much more inter-related than we could have ever imagined in the past.

If one considered issues relating to face recognition and the interaction of children with autism and their caregivers, the assumption of little or no communication among the various parts of the brain in these children would certainly help explain issues in “facial interactions”. Functions of “face recognition” resided in the temporal lobe. Yet, visual attention functions resided in the parietal lobe, and visual processing resided in the occipital lobe. As such, several parts of the brain were involved in the simple act of “face recognition and facial interaction”, and, needless to say, if those parts of the brain were not communicating properly, it would not be surprising that children with autism would have tremendous difficulty in this area.

What was known about these children, however, was that in looking at the face, they very much tended to focus on the mouth of the person speaking. Again, this was not surprising to me given that auditory processing and the understanding of speech were co-located in the temporal lobe along with face recognition. Thus, it made perfect sense that a child attempting to “break the code” to language would focus on the mouth of the person speaking. The same was also true of persons who were deaf and who learned to “lip read”. Their auditory processing was impaired, and yet, they chose to try to decipher language in others by “lip reading” – again, focusing on the mouth! Auditory issues were clearly documented in children with autism and although, like Zachary, their hearing usually indicated they could hear, there certainly appeared to be certain frequencies that were more bothersome to these children.

As I discussed matters of “hearing” with a man who was losing his hearing, he commented to me that even with a hearing aid, he often could not hear what was being said by those next to him because of the “background noise”. “Background noise” had been the major issue in his hearing loss. Could it be that in children with autism, they too heard the “background noise” more? Could this possibly play into the fact that these children were so easily distracted and had an “attention deficit”? Perhaps. The more I looked to my son for answers to his autism, the more many other things made sense, too!

For example, in looking at echolalia specifically, clearly one needed to be able to “understand language” to communicate. But, how did one come to learn anything – be that language, a skill – or pretty well anything else? Repetition!

It was well documented scientifically that the solidification of “memories” was very much impacted by repetition. In other words, the more you practiced something, the more easily you could do it. The more you practiced or repeated in “language” matters, the more easily you could remember it (i.e., memorizing a poem, learning new words, a new language, etc.). Clearly, for example, the more often I used “a new word”, the more easily I remembered that new word and its meaning. What was “echolalia” if not “repetition of language” – repetition that in my opinion, was the child’s way of coming to understand and solidify language – both the words themselves and the “when to use this word”. In other words “echolalia” was nothing more than the building of “references” as they related to the development of language – and hence, the term “reference communication” to describe what I had so clearly come to understand Zachary’s early speech development.

Not surprisingly, Zachary no longer engaged in echolalia. Echolalia, in Zachary, had disappeared as his understanding of language had increased. Now, when he ever repeated a word, it was because it was “a new word” and that “repetition” was usually accompanied with “spell …., mom” (with the “…” being the new word). When I spoke, or anyone else spoke, if the words used were words Zachary already knew, he did not repeat them.

Obviously also involved in language development was the function of auditory processing – also located in the temporal lobe. Note that although certainly a “plus” to language development, a child could be deaf and still have an understanding of language. As such, although “desirable”, auditory processing certainly was not “a must” to the “understanding of language”. It was very interesting that although the “understanding of language” was located in the temporal lobe, the “production of language” was located in the frontal lobe – along with motion, smell and control of emotions – all functions I now believed to be much more inter-related than we could ever have imagined.

The sense of smell was discussed at length in both book two and book three and would be discussed somewhat later in this text. The point I wanted to make here, as smell related to communication, however, was that clearly, smell did play a role in communication as well. This was clearly evident in the animal kingdom. Yet, a person could hold an orange in his hand, and have an understanding of what that was simply based on smell and/or touch. The sense of smell had functions located in both the frontal and temporal lobe – parts of the brain that clearly involved language functions also. Likewise, I could hear a bird’s song and know that this was “a bird” without having to do anything – myself.

Simply smelling something or hearing something provided “some form” of communication or understanding in and of itself. I think that society made a huge error in assuming that the lack of a response meant “no understanding” because, clearly, that was not the case. As I considered the fact that the “understanding of language” was in the temporal lobe and the “production of language” – for example, a verbal response – was in the frontal lobe, this only made even more sense in my opinion. Clearly, production and understanding were two very, very different things! I could simply smell or hear something and have a complete understanding of “what that was” without – myself – showing a response (i.e. verbalization) – and I suspected many children with autism understood much more than we could ever imagine, too!

Note also that to “produce language” did not require working eyes, ears or vocal cords – indeed, language production and understanding could be based completely on – motions and/or touch. I very much suspected that this was why sign language appeared to work for many children with autism who were non-verbal.

Zachary always loved learning anything that involved motion. I had only started to teach him some of the basics in sign language. He was always very, very excited to learn new words such as “stop” or “go” in sign language and then play with me as we applied those signs or motions during our playtime outside. I had started to use motions in working more with Zachary in the area of safety and crossing the street and had found that he understood concepts much better if I made use of motion such as sign language. This was all very, very new to me, and as such, I still had a great deal to learn in this area, but, I certainly could see the potential that existed in terms of communication with children with autism via the use of – motion! In my opinion, this was truly one of our most untapped tools yet, perhaps one of our most effective tools in communicating with children who have autism! Motions could certainly be used to teach many, many concepts. This was not to say that verbalizations were not also important – clearly they were - however, what I was saying was that motions were a valuable component that should be included with other methods in attempting to communicate with the child who had autism.

In my opinion, it was important to use as many forms of communication as possible. For example, if a child had shown any ability to verbalize sounds there was hope there. Granted, cerebellum damage could impact one’s physical ability to speak, yet, the cerebellum continued to develop until the age of twenty or so and as such that provided hope that perhaps, even in the case of cerebellum damage actually impacting the motor functions involved in speech (i.e., physical nerve or muscle damage), there could be the ability to later down the road come to overcome some of these limitations as well. If there was one thing I had come to understand in this journey with autism, it truly was that the human brain and body were amazing indeed in their ability to adapt to injury. Thus, if one approach did not work, perhaps another would.

As such, I would encourage as many different ways as possible in attempting to reach these children by using not only motions, but phonics, word associations, etc. to help these children break the code to communication. It could take a lot of work to get that “first crack” in the shell, but once that “first crack” came about, it certainly opened great doors of opportunity. Society had seemingly given up on so many of these children, yet, I knew that no matter how difficult things could be, past, present or future, I simply could never give up on Zachary. I knew there were still many challenges ahead, but, those would be things I simply had to deal with one day at a time.

As I had stated earlier in so much in the life of the child with autism, it appeared that stimulating as many parts of the brain at once was key to their understanding, and given that motion was a valuable tool for communication – one that already existed and was very well developed – in my opinion, this avenue was perhaps one of the main keys to unlocking the doors of communication with those children with autism who were still so completely in their own world. In my opinion, motions would in all likelihood help with the understanding of many concepts for these children – whether verbal or not.

One could be deaf, mute and blind and still learn to communicate. Motions did not have to be “seen” – they could also be “felt”. As such, making specific motions in the palm of one’s hand, for example, certainly was a way of establishing communication with a person who could not speak, hear or see. Everyone could pretty well “feel” something on the skin – and that “something” could certainly be “the feeling of communication motions”. Thus, clearly, motion and language production were absolutely tied to one another. If one could not “feel” something on the skin, if that person was also blind, deaf and mute, then, what “other options” were available for communication? I could think of none. As such in order to be able to “produce language”, you had to at least be able to “feel language or communication motions” on the skin.

Thus, in looking at language production it would be very, very difficult to obtain “language production” in a person who was blind, deaf, mute and who had no feeling whatsoever in the skin. But, I knew of no one that was “that impaired”. Note that a person could be paralyzed from the neck down and still be able to have “feeling” on the skin found in the area of the face. As such, it appeared almost impossible to be completely without the ability to “feel something” via the skin. And, as such, the skin, and the sense of touch was absolutely key to language production in persons with impairments in sight, sound processing, and/or speech. The one thing that appeared to be “unfailing” when it came to the ability to produce language was the ability to “feel language”.

As such, in persons with all kinds of disabilities as they related to communication, one of the critical keys was motion – and hence – sign language! It was because of this that I now felt sign language should be taught to all children in school because, if someone became disabled later in life in a manner that impacted actual speech vocalizations, sight, or sound production, one thing that a person could fall back on was the ability to at least be able to “feel or see the motions of language”.

As stated in my second book, this was also seemed to provide the reason so many of us instinctively “used our hands” and “motions” when we talked.

Although motions were very, very, important, it was also necessary to keep in mind that, in a child with some verbal ability, perhaps they should be varied somewhat. The reason I stated this was because if a child had any verbal ability that meant there was hope in helping that child to actually talk. Yes, sign language should be used, but when dealing with children who had the ability to speak somewhat, although motion, it appeared could be key to language production and word associations (all in the frontal lobe), the understanding of language appeared to be tied more to auditory processing since both those functions were co-located in the temporal lobe.

Thus again, would it not make sense that functions that were closely linked – physically – in the brain, were probably located “together” because they impacted one another more than did functions located in other parts of the brain. It just seemed to make sense to me that neurons most closely tied together would most “interact” together.

With Zachary, I had always done things like “acting out letters” with my body parts as I called them out. I had worked on teaching him to understand the alphabet in many different ways – the computer, singing and acting our songs, puzzles, and body part motions. There were also good suggestions in The Phonics Handbook by Sue Lloyd that could be used to teach the alphabet and associated phonics.

My concern with using “just constant or repetitive motions” was that if a child had the ability to speak and yet motions were better understood, I wondered if a child would come to prefer to simply “use motions” and use speech less – even if the ability for speech was there. I did not know. In my opinion, it was important to teach the same thing – the same concept (i.e., the alphabet) - in many ways to show the child that “the concept” was key – not the motion or method. In so much, for Zachary I soon saw it was “teaching of the concept” by using co-located functions that was key - to breaking the code!

In trying to get actual language production - actual verbalizations – in children with autism – especially children who had shown the ability to utter - “something” – I truly felt “multiple ways” had to be used. The idea was to show the child that the “constant” was “the concept” (i.e., the alphabet or the letter-sound association, etc.) as opposed to the motion itself for example. Motion was critical – of that, I had no doubt – but I also recognized the need to help move these children toward actual verbalizations if possible also. Sign language could be a powerful means of communication when no other communication was possible, but if other means of communication were possible one had to maintain hope of developing those capabilities also in these children.

Although language production seemed very much related to motions – both functions in the frontal lobe - the understanding of language was located not in the frontal lobe with language production, but rather in the temporal lobe with other functions. When one really started to look at those functions co-located in the temporal lobe along with the understanding of language, clearly, many, many of these functions appeared to be so very inter-related.

With Zachary, tools I had used (like the video I came to call “the alphabet train” video – a video that was actually entitled The Miracle of Mozart ABC” by Babyscapes, and available at http://www.babyscapes.com/ourvideos.html), had made use of both sound and motion – and specifically of sounds that provided for “letter/sound associations” – something that surely could “tap into” functions of “word associations” that were co-located along with language production in the temporal lobe. Note that auditory processing, the understanding of speech and categorization functions were co-located in the temporal lobe and as such, this video also very much “tapped into” those functions as well. Also note that “word associations” (frontal lobe) were nothing more than “very specific categorizations” (temporal lobe function) and as such, word associations, provided, in my opinion, the critical key to bridging the frontal and temporal lobe functions – the critical key to bridging language production (frontal lobe) and the understanding of language (temporal lobe).

Language production (frontal lobe) clearly could occur “without making sense” to someone else. For example, I could speak or babble and not have anyone around understand me. A person could produce vocalizations that made absolutely no sense to anyone else. A newborn child could “babble” without having a clear understanding of language. Thus, language production, in and of itself could in my opinion, occur without an understanding of language. As I thought about Zachary’s language development, I realized that the key was that, too often, we interpreted things like echolalia as “meaningless language”, but perhaps, it was only meaningless to the person listening and that it was actually “just a step” in the acquisition of language skills. The goal was to move from “just production” of language to an understanding of language in the sense that “others” – not just the child – could understand it also. Although Zachary had been unable to actually “produce language” for quite some time, I suspected he had been able to “understand” a great deal of it for quite some time also prior to actually “producing it”.

Understanding what was important to the understanding of language and how that understanding was acquired appeared to be very key.

Again, I could not help but think that co-located functions had to be “more inter-related” with one another than perhaps we had ever imagined – and that meant that if this were true, those functions key to understanding language had to be co-located with “understanding of language” functions – and that meant – “other” temporal lobe functions simply had to be key to understanding language. Likewise, “other frontal lobe functions” had to somehow be key to the production of language. And, the challenge – and indeed, perhaps the answer to issues of speech in children with autism - came in “bridging the two” via “similar functions” such as “word associations” (frontal lobe) and “categorizations (temporal lobe) that could act as key link to help rebuild connections that, in my opinion, very much appeared to have been severed.

The understanding of language was a temporal lobe function, co-located with memory functions and auditory processing. But, the understanding of language was also co-located with other functions in the temporal lobe – and in looking at those functions it truly appeared to me that almost all functions in the temporal lobe had something to do with the understanding of language.

For example, the temporal lobe also included functions involving emotions. Clearly, emotions were tied to the understanding of language. As described in book two, often, a person that experienced great sadness or trauma often appeared as though they lost the ability to understand what someone was trying to tell them. It was often as though “they were failing to hear – failing to understand” what was said. Likewise, a person experiencing great fear or stress often failed to understand language as the “emotion” took over. There was no doubt that often it was very, very difficult to “reach” someone who was in a heightened state of emotion – as such, it was difficult to “make them understand”. Note that “control of emotions, however, was not located in the temporal lobe – but in the frontal lobe – along with actual language production.

Note that emotion functions were located in several parts of the brain - the temporal lobe and amygdale (part of limbic system) as well as in the frontal lobe (control of emotions). Of these, key in the understanding of language was the ability to perceive emotions in others – a function that resided in the amygdale. The amygdale was known to synapse directly with the frontal lobe (where resided “language production” functions). There was no doubt that the ability to perceive emotion in others was also key in the understanding of language – a temporal lobe function. If this part of the brain - the amygdale - was not communicating properly with other functions relating to the understanding of language (temporal lobe), and/or production of language (frontal lobe), clearly, the understanding of language and/or the production of language would be somewhat impaired.

Perceiving emotion in others could involve both sight and/or sound (i.e., tone of voice). Note that voice recognition was co-located in the temporal lobe along with the understanding of language. As such, this very much explained why Zachary always understood emotions better when they were specifically verbalized to him. Yet, his visual understanding of emotions and how those played into the understanding of language was clearly impacted.

For example, on many an occasion, I had cried with Zachary in the same room. In fact, I could be sitting right next to Zachary and crying my eyes out and he simply paid no attention to me whatsoever. Yet, if I verbally said: “I’m a sad mom”, that immediately grabbed his attention and he always felt upset when I told him – verbally – that I was upset. As such, if I said “I’m a sad mom” and I was across the room from him, he would rush over and attempt to comfort me. Yet, if I failed to verbalize my emotions for him, it was as though he simply did not “see them” or “understand them”.

The same situation existed if I said: “I’m a mad mom”. Zachary knew that he was not supposed to do something that would result in a “mad mom” and as such, often, to get him to listen, all I had to do was say “if you do that, I’m going to be a mad mom… if you want a happy mom, you have to…”. Thus, when it came to the understanding of language and perception of emotions in others, clearly, verbal cues were much more powerful to the understanding of language than visual cues.

Likewise, I had stated in my second book, that when Zachary was shown a picture of himself when he had a horrible rash, he had failed to recognize that it was him in the picture. To Zachary, this could have been any child. Yet, when – told – that “this was Zachary”, he experienced tremendous distress. When – told – this was “him”, he – understood – it was “him” and it had been as though that had triggered a memory recall of the experience itself – and as such, his reaction to the picture was amazing in that it appeared to be worse than having gone through the experience itself. Yet, had he not been – told verbally – that his was “him”, there would have been no reaction to that picture.

Thus, clearly, the understanding of language was tied emotions and memories and was very much dependent on auditory processing.

I was happy to say that since I had worked on issues of emotion with Zachary, he had made tremendous progress in this area as well. Now, just a “sad face” was usually well perceived – as were many “other faces”.

Recently, as Zachary read a book we both truly enjoyed, I had noticed something rather interesting. Zachary was now beginning to have much more expression as he read. This particular book was a favorite for both of us – The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein (ISBN 0-06-025665-6). Although we both loved this particular book, we did not read it that often only because I always wanted to provide variety for Zachary. I never wanted reading to become “just memory recall” as it apparently was in so many children with autism – children who had a fantastic ability to remember entire books word for word. I had many, many books for children – literally bins full – and as such, providing variety for Zachary when it came to reading materials was not a problem. Yet, every once in a while, we would pull out “an old favorite” - The Giving Tree.

As I listened to Zachary reading the story to me, there were times when his voice had that monotone sound – that flat, no expression to it tone that almost all children with autism seemed to have. Yet, at other points in the story, Zachary truly showed proper intonation as he did the proper voice fluctuations in reading say, a question, in the text. He also showed emotion in his reading in parts of the story. It occurred to me that as Zachary was exposed to the story on several occasions, he had to now have a much better understanding of things like the “emotion” in this story and as such, I felt this was why he could now express that emotion in his reading of the text. Note that he also had a better understanding of words that introduced “a question” and as such, his intonation certainly had to be impacted as he now recognized more “question words”. Note that memory and emotion functions were co-located in the temporal lobe along with the understanding of language.

As I thought about Zachary’s reading of this text, clearly, again, so much could be explained by my theory of little or no communication among the various parts of the brain in children with autism. So many of these children were known to have the ability to read something – language production (frontal lobe) – and yet, could have no understanding (temporal lobe) of what they were reading. As such, language production (frontal lobe) could be there without the understanding of language (temporal lobe). Likewise, a person could understand language (temporal lobe) and not be able to verbally express that understanding via actual language production (frontal lobe). Also, language production and emotions were found in separate parts of the brain and as such, certainly, this had to play into the issues of proper tone or flat tone in what we saw in these children. Production of language – the actual verbalization of words – was located in the frontal lobe, yet emotions were found in the temporal lobe/amygdale parts of the brain. As such, again, if these areas were not communicating properly, certainly, this had to have implications for the expression of emotions in speech production. I also suspected Zachary’s love of onomatopoeias was due to the fact that these words were usually spoken with a great deal of expression and/or emotion. Words like “crack” or “squish” or “brrrrr”.

Also, goal directed movement, visual attention, the sense of touch and manipulation of objects were co-located in the parietal lobe. Note that I did not have to hear, smell or taste to be able to read Many of the primary functions needed for reading appeared to be located in the parietal lobe including the ability to integrate sensory input into a single concept. Indeed, reading difficulty was a sign of parietal lobe damage. The inability to recognize words and symbols was a sign of occipital lobe damage. The occipital lobe was associated with visual processing. Clearly, visual processing was an important contributor to the proper understanding of the written word, but it certainly appeared that the function of reading – in and of itself – “reading production” – appeared to be a function not of the occipital lobe, but of the parietal lobe. I could “read” without sight, for example, by using Braille – a “reading” system based on touch. Of course I was not saying that sight was not important to reading – clearly it was – but, it was not “absolutely critical” – I could still read, without sight if I made use of the sense of touch!

Thus, much as the production and understanding of language were found in separate parts of the brain, the frontal and temporal lobes, respectively, so too, did it appear that the “production of reading” and “understanding of reading” could, perhaps, be found in different parts of the brain, the parietal and occipital lobes, respectively.

If this were true, it appeared that to get “production” or actual “reading” to occur in a verbal child (one who could speak), one had to focus on those functions located in the parietal lobe. Yet, to have that “understanding” of what was read (not spoken), it appeared the functions in the occipital lobe (i.e., identification of color, locating objects in one’s environment, ability to recognize words/symbols, etc.), were more important.

Parents of children with autism often clearly indicated that their children often had the ability to read (production of reading) but failed to understand what they read (understanding of reading). Perhaps we now had a better understanding of why that was when we considered that language was nothing more than “symbols” that had to be understood… and to understand symbols – or written language – it had to be categorized – and categorization of language symbols resided not in the parietal or occipital lobe – but in the temporal lobe. As such, clearly, all lobes, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital had to be properly communicating in order to achieve both the production and comprehension of language. Indeed, if connections had been severed, in my opinion, the way to “rebuild them” had to be in finding “bridging” or “similar” functions across each area involved in speech.

As I completed this text, an interesting study had just been done in England. It appeared that – at least in the English language – as long as the first and last letter to a word were in the correct place, that the brain could “fill in” the other letters and still understand “the writing” – or the written word.

This was indeed all very interesting, especially since I knew that children with autism also often had dyslexia (i.e., making a “b” instead of a “d”) and that the ability to distinguish between left or right was also a parietal lobe function.

Note that damage to the parietal lobe resulted in reading difficulty and the inability to differentiate properly between left and right. Yet, the inability to recognize words or symbols was a sign of damage to the occipital lobe – responsible for visual processing.

I had heard of this study on a message discussion board, and no one seemed to have the link to the original study. However, the study apparently had shown that it did not matter whether or not the letters in a word were in the right place, as long as the first and last letters were in the correct location, the brain could still make out the text and a person could still “read” because humans apparently did not see words as “individual parts” but rather, saw words as “wholes”.

Gvien evreyhtnig I had cmoe to udnresatnd in Zcahray in trems of his need to udnresatnd “the prtas” bferoe the “wohle” mdae snese, nedelses to say, I fuond tihs vrey, vrey itneerstnig idneed. I kenw Zcahray to be an ecxelelnt raeder, and that maent he had to hvae the aibilty to see “wohles” acrcoridng to tihs sutdy. Did tihs smilpy maen raednig was a rgiht barin atciivty bceuase the rgiht barin porcsesed “wohles” as opopesd to “prtas”? If taht was the csae, taht smilpy maent taht Zcahray’s “raednig fnuctoins” had not been ipmarierd”.

Alright… that was as much as I could type to give you an idea as to what this study was saying… especially given that word processing packages automatically corrected errors… it had taken me a long time to type just that one little paragraph. :o)

Again, this was all very, very interesting. A sign of occipital lobe damage – responsible for visual processing - was the inability to recognize symbols or words. Clearly, Zachary could recognize words and read very well. But, did that mean that “he” was reading the way a normal person did – apparently, seeing words as “wholes” or was he taking “the parts” to come up with the wholes? The reason I asked this was because although I knew Zachary to be an excellent reader for his age, another sign of occipital lobe damage was difficulty in drawing, etc., and clearly, with signs of dyslexia showing up in my son’s writing, that could indicate “issues with drawing”.

Of course, issues with drawing were also a sign of parietal lobe damage as was difficulty with eye hand coordination, difficulty with reading and difficulty in determining “left from right”. Interestingly, Zachary had no problem with differentiating “left from right” in “other things” – things that did not involve writing.

Zachary could easily read or recognize words and yet, when it came time to write his letters, clearly, there was some dyslexia there. Issues with eye/hand coordination and left/right distinction, both signs of parietal lobe damage, certainly appeared to be at play in dyslexia… but were they? If life was not already complicated enough at times, now I had this additional, yet very intriguing, puzzle before me as well.

As I considered “the written word” that was read – clearly, Zachary’s reading – especially for his age – was excellent. Right vs left did not seem to matter much – if indeed that was a problem for him. But yet, when it came to actually writing something – a motor function – then, the “left vs right” was absolutely an issue. That was all very interesting to me given it seemed “written language production” – writing itself – was very much a function that required input from the frontal lobe (the motor cortex). As such, Zachary could easily read (written language production), but could not easily “produce” language from a motor perspective. Note that language “production” (what I had simply thought was verbal language production) was a function of the frontal lobe – but, now, I wondered if this “language production” was not also “language production” for the written word also.

Thus, there were many, many aspects to “language production”. It could be verbal language production (frontal lobe) or the production of language having to do with the written word – reading (parietal and occipital lobes) or it could be “language production” in the sense of writing itself (a function that clearly involved the motor cortex - also located in the frontal lobe). Note that when it came to “reading” – I could read without sight (using touch as in Braille) but I could also read without actually verbalizing something – without actual speech production (frontal lobe) and hence simply “read quietly”.

“Reading” could be viewed as a different type of “language production” – a very specialized form of language production and language comprehension that involved the written word as opposed to the verbal word! And, just as areas for verbal language production (frontal lobe) and comprehension (temporal lobe) had to be properly communicating, so too did written language production or reading (parietal lobe) areas of the brain and written language comprehension (occipital lobe) areas need to be properly communicating as well! This could certainly all get rather confusing – but it certainly was all very interesting also. Clearly, language and/or communication in humans involved several major parts of the brain and it could get rather complicated – rather fast. For language and/or communication to occur, these various parts had to have the ability to properly communicate with one another – something that clearly was not happening in many children with autism.

Yet, as confusing as all this could be, the one thing I now absolutely saw without a doubt was that most critical of all had to be the ability to properly – categorize language – whether written or verbal!

A person had to be able to “categorize” what he said, what he understood in terms of spoken language, what he read out loud (production of written language) and what he understood in terms of “written language” (reading quietly). To make sense of anything in life – it had to be - categorized!

Thus, in teaching a child with autism, in my opinion, one had to first determine whether or not the issue was one of verbal communication or written communication and then look at functions co-located with each of these in order to work on the desired behavior or function. Thus for verbal language functions, I believed one had to make use of bridging functions between the frontal and temporal lobes whereas in written language functions, one had to perhaps focus more on bridging the occipital and parietal lobes when it came to actually reading a text but on bridging parietal (eye/hand coordination) and frontal lobe (motor) functions when it came to actually producing written words (writing). Clearly, “to write” did not necessitate I need to understand “what was being written” and as such, it was not, in my opinion, the occipital lobe that was key to overcoming “issues with writing” but rather the bridging of the frontal and parietal lobe functions.

To understand both the written and verbal communication, it appeared required the bridging of the temporal and occipital lobe functions. Given that “vision” bridge available to join temporal and occipital lobe functions and that the only functions relating to vision in the temporal lobe had to do with “face, place and body part recognition”, I was now beginning to understand why teaching language by using “body parts” had worked so well for my nephew Andrew and why children with autism so often focused on – the mouth – as opposed to the eyes. The eyes could provide very little in terms of “breaking the code to language”, but the mouth – now that was something worth investigating for a child attempting to break the code to language!

Again, this certainly could help explain why these children were often such excellent readers and yet had difficulty in other areas of “communication” and why they so very much, focused on – the mouth of others - as opposed to the eyes! The mouth in and of itself provided many insights into language for these children. Of that, I had no doubt. The eyes, although they provided some “non-verbal communication” also required bridging over to the amygdale – yet another part of the brain. As such, it seemed the eyes – for these children – were less important in “breaking the code”.

When it came to difficulty in understanding language, perhaps we needed to keep in mind that a “question” posed to a child verbally would involve the understanding of verbal language as opposed to the understanding of written language. It certainly would be interesting to study how well children with autism understood the written verses the spoken word and how using methods providing for the “categorization” of language could help with these issues given such methods could provide a variety of options to help activate as many parts of the brain as possible [more on language categorization later in this text].

Also, I had noticed that if Zachary hesitated in any way or if his attention was diverted, all I had to do was spell the first word in the next sentence or say it, and he would then keep going. This was very much parallel to the fact that hand over hand techniques also worked well with these children. In hand over hand techniques, all one had to do was do the first motion and usually, the child could go on to complete the motor task required. Note that motor functions and memory relating to motor functions were co-located in the frontal lobe along with speech production. As such, it made perfect sense that methods that paralleled hand over hand techniques in the area of speech production would work very much in the same way as they did with motor activities or in functions such as “reading”.

In looking at “reading” I now understood why this task came rather easily to children with autism – clearly it involved many, many aspects of the brain and as such, reading had to be an area or function that could more easily be “decoded” by the child than were perhaps other functions. The more tools one had available for “decoding”, the more likely the probability of success.

The other thing I had come to understand was that Zachary showed great enthusiasm in reading specific types of words – words like “CRACK!” or “vvvvrrrroooooooommmmm” or “buzz” – words that sounded very much like the actual sound – something known as onomatopoeia – where the words seemed to imitate the actual sounds associated with the objects or action they refer to. Zachary absolutely loved reading and/or hearing words like these. As I thought about that, this too appeared to now make sense given that auditory processing and the understanding of language were co-located in the temporal lobe. What words would be best understood (temporal lobe function) if not words that sounded (temporal lobe) just like the actual thing (memory also in temporal lobe)? These words also very much activated the frontal lobe given that the language production in the vocalization of these types of words in particular provided a very powerful word association – an association that appeared to bridge the frontal (word associations) and temporal lobes (auditory processing, etc.).

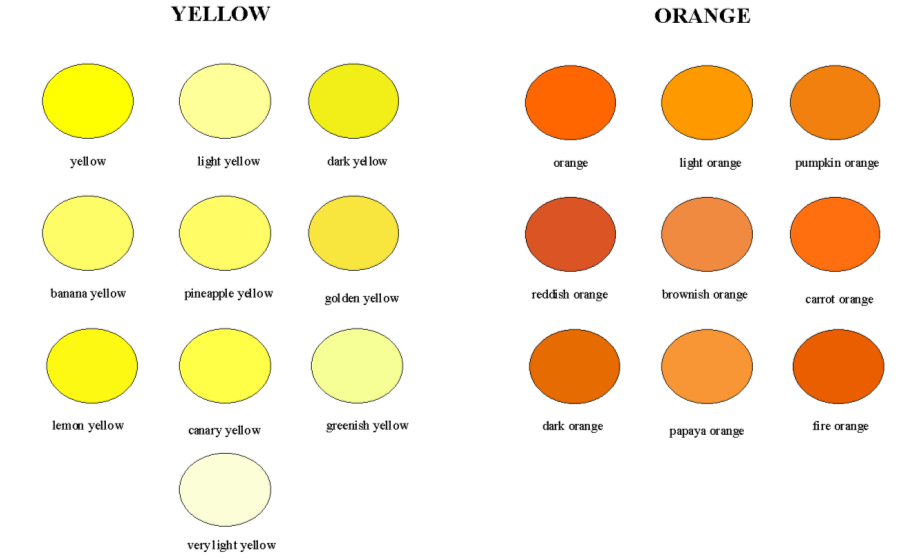

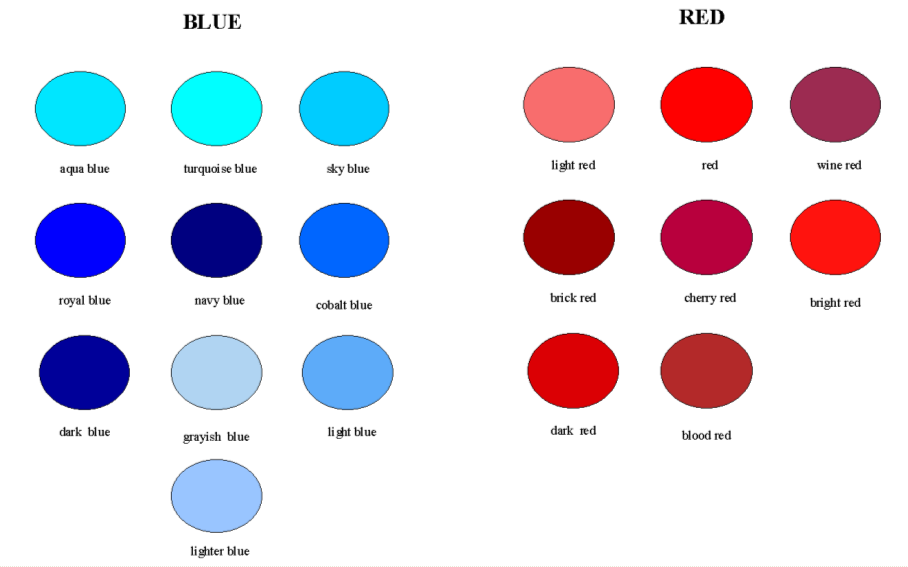

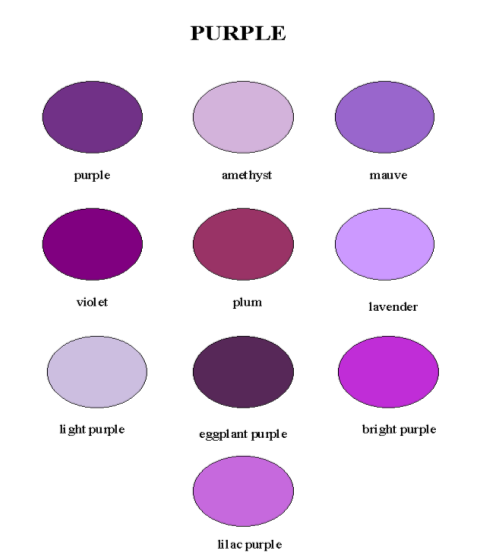

But, there were other things Zachary clearly also loved to read… anything having to do with color for example, or the repetition of words like: “up, up, up” or “down, down, down”… or the reading of opposites. Small phrases like this involved repetition but also could easily trigger one’s imagination in that it was very easy to picture these things. Production of language (actual verbalization of these small phrases), imagination and word associations (i.e., opposites) were co-located in the frontal lobe and as such, I was not surprised that Zachary loved to verbalize such words.

Given my concerns over “pretending” – as clearly expressed in both books two and three, I was always certain to make sure that I explained to Zachary the difference between real and pretend in anything involving “imagination”. For persons who had not read books two and/or three, my concern here was that imagination and the concept of self were co-located in the frontal lobe yet the ability to distinguish between truth and a lie was located in the temporal lobe. As such, if the two were not communicating properly we had the makings of a very nasty situation indeed – a situation whereby a child could literally lose his sense of reality as he engaged in imaginary play. Yet, although I had major concerns with this issue of imagination and the concept of self, there was no denying that in the simple act of reading books a great deal could be learned in order to help these children.

Repetition was involved in memory (temporal lobe) formation and memory formation in the understanding of language (also in the temporal lobe) and as such, small phrases such as these – “up, up, up”, or “down, down, down” - appeared to also activate both the frontal and temporal lobe at once.

All this certainly had huge implications in terms of the types of books we should be using to teach these children – the types of books that could perhaps best maintain their interest.

All of these things, undeniably, were very, very interrelated and very much tied to not only the understanding of language, but to the actual production of language as well, as clearly, there were “some things ” – key words, key phrases, key associations – that simply produced a much greater reaction and interest when it came to actually producing language in Zachary.

Likewise, I had no doubt that emotion itself (temporal lobe) and emotion perception (amygdale) and control (frontal lobe) – or the lack thereof – also played a role in language production and understanding. These would be discussed in greater detail later in this text in a section dealing specifically with emotion in communication.

Also co-located in the temporal lobe with the understanding of language was voice recognition. Whose voice did one not recognize most if not – my own. As such, again, “parroting” or echolalia in children with autism, again, seemed to make sense when looked at in terms of the understanding of language and the theory that co-located functions could be much more inter-related than we may have ever imagined. Likewise, a child understood and responded most to the voice of a parent. Something said in the same way, to many persons at once, could often mean different things to different persons, yet, persons who knew each other usually understood exactly what one was saying when to someone else, someone less familiar with the speaker, there would appear to be “more confusion” as to the understanding of what was being said in spite of the “same tone” having been heard by all. Clearly, very subtle differences in tone could often also make a huge difference in what was being said or implied.

The function of face recognition was also co-located in the temporal lobe with the function of the understanding of language. There was no doubt that “those we knew” and “recognized” were those we best understood. Indeed, persons who knew each other well could very much communicate with facial expressions or “certain looks” only. Husbands and wives could “understand” what the other was “thinking” before any communication seemed to even exist. I knew that with my own husband, there had been countless times when we had been thinking about the very same thing at the very same time. Yet, it was always harder to understand “a stranger” and know what “they were thinking”. One certainly could have either an accurate understanding of another person based on “first impressions” but one could also be very, very wrong also. Thus, again, there could be no denying that both voice and face recognition clearly played a role in the understanding of language.

Closely tied to face recognition was the function of visual perception that also existed in the temporal lobe. Note that, interestingly, most visual functions were located in the occipital lobe. Indeed, the occipital lobe had functions that appeared to be related solely to sight. The frontal lobe appeared to have no visual functions at all. That was indeed very interesting given this was where “language production” was found. And hence, again, this certainly showed that language production was not dependent on “vision” and yet, in trying to produce language in children with autism, we often used visual cues. Perhaps this was one of the reasons so many were still “non-verbal”.

Also interesting was that visual attention was found not in the occipital lobe with other critical vision functions, but in the parietal lobe with somatosensory (body sensations) processing, spatial processing, touch perception, manipulation of objects, goal directed movement, 3 dimension identification and what appeared to be a very key function - the integration of sensory information that allowed for the understanding of a single concept – in other words – the integration of the “parts” into the “whole” – what I saw as one of the major issues in children with autism.

Although most of the visual functions in humans were in the occipital lobe, clearly, certain visual functions were located outside of this region. As such, I could not help but ask why that was. In my opinion, the visual perception in the temporal lobe, a visual function co-located with the understanding of language, had to be related to other functions in that area – and that very much included the understanding of language. Note that visual perception in the temporal lobe was associated with the recognition of faces, places and body parts. As such, again, I truly felt that visual perception in the temporal lobe was somehow very much related to the understanding of language and that in trying to have children with autism understand language, those “visual cues” had to involve, in my opinion, face, place and body part recognition “visual cues”. In other words, using body parts to help with the understanding of language. Looking back, that had been exactly what I had done with Zachary in labeling so much for him… I had used my hands to physically touch everything as I showed it to him… and I had used his hands to make him touch everything also. I had used my body to “form letter” (best I could :o) ). So much I had done had involved – my body – just as had the phonics program my sister-in-law had used to teach her son – phonics!

In my opinion, this involved more than just “recognizing a person” when it came to the understanding of language. There was no doubt that a child best recognized and understood his parent. Yet, the child with autism had also revealed something else that appeared to be very key. In matters relating to communication the child with autism focused not on the eyes of another person, but rather on – the mouth!

The deaf often quickly learned to “lip read” in order to communicate. How very interesting indeed that, children with autism focused not on the eyes of a person, but on the mouth! In my opinion, this again, was an attempt to “break the code” to communication.

Again, this seemed to indicate that motion and voice recognition was key to communication. Note that “voice recognition” could take on a couple of forms. Voice recognition functions definitely involved recognizing a “familiar person”, but they also appeared to involve recognizing “familiar sounds”. Again, auditory processing was also co-located in the temporal lobe with the understanding of language. Clearly, sounds (or lip motions involving face recognition and visual perception also in the temporal lobe) had to be recognized to be used in helping with the function of the understanding of language. Sounds that were not recognized were simply not understood and recognition required repetition and categorization for the understanding of language to occur. As such, again, in echolalia, it was my belief that what we were seeing was the repetition and categorization functions so necessary to the understanding of language – the repetition of sounds (auditory processing) from familiar faces and voices – all temporal lobe functions!

Clearly, a normal child in language development repeated words spoken to him by his/her mother. Repetition helped solidify memory in almost everything and as such, it made perfect sense that children with autism would repeat everything they heard at first – much as would any child going through the normal steps of language development. In my opinion, what we were seeing in “echolalia”, as such, was much more than simply “parroting”. This simple act of repeating what was heard clearly activated almost the entire temporal lobe. Echolalia was the building of references for future use and a critical language development step that - because it occurred in “older children” - had simply not been recognized for what it truly was in children with autism.

Also co-located with the understanding of language in the temporal lobe was the categorization of objects. Of all the functions in the temporal lobe, perhaps the most critical of all for children with autism was that of – categorization - for within “categorization” was the ability to “order one’s world” - to make sense of it – to “break the code” – to almost everything in life!

Although at first glance it appeared that this was a function relating to concrete objects, clearly, the categorization of objects was absolutely key in the understanding of language also. To make sense and be understood, words were “things” that also had to be categorized. The word “sad” meant something very different than the word “jump”. As such, in order for language to be understood, it required not only that I be able to categorize it but that the person communicating with me also have this ability. For the child with autism it was critical to help with “categorization functions” as they related to language as this would certainly help with the greater understanding of language in these children.

As such, when I presented Zachary with a new word, I now usually always helped him to categorize it by providing for him things like the spelling of that word and a definition of that word. Examples of “how to use the word”, were also critical!

Note also that the processing of music was also located in the temporal lobe. Many studies had now indicated that music therapy was helpful for those with autism, Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia. Zachary always loved to be sung to. Indeed, if my theory of heightened communication and inter-relationship among the various functions co-located in a specific part of the brain were correct this indeed, would argue that music was also somehow tied to the understanding of language. From the time both my children were very small, I had always played classical music for them as they went to sleep – calming music, such as that of Mozart.

Mozart had composed music from as early as five years of age and his music, unlike perhaps other forms of music, was believed to help in activating neurons that stimulated very specific pathways in the brain that helped increase receptivity and retention in learning. The “Miracle of Mozart” video series by Babyscapes, Inc. were produced based on these studies (www.babyscapes.com, 8391 Beverly Blvd, #276, Los Angeles, CA 90048, USA, 888-441-5437). Babyscapes, Inc. had produced that Miracle of Mozart ABCs video – “the alphabet train video” – Zachary still loved to this day!

Music had indeed always been important in Zachary’s life.

A song was a grouping of words and/or notes. It had a beginning and an end and usually, some kind of “pattern”. The word of a song was always followed by a specific word – in other words, the song stayed the same – its words did not change over time. As such, a song could easily be memorized and recalled. These factors helped explain why children with autism, such as Zachary, loved songs. They were “language” that was “already categorized” and did not change. This also explained why my son used to scream if the radio or CD in the car was turned off in the middle of a song. Children with autism seemed to always need that “all or nothing” and had no room for the “in between” in anything, and herein was the key to so many issues I had seen in my son.

Note that loss of flexibility in thought was a sign of frontal lobe damage. The frontal lobe was associated with motor functions (perhaps explaining also loss of flexibility in motor functions, ie., obsessive-compulsive behavior and repetitive behavior), the production of language (perhaps explaining loss of flexibility in speech and the need for “sameness” in speech production), olfactory functions (perhaps helping to somewhat explain lack of flexibility in food choices), control of emotions (perhaps explaining lack of flexibility in emotional responses – i.e., the “all or none” extremes in emotions so often seen in these children and the desire for only one “acceptable” emotion – i.e., “happy mom”), and the assigning of meaning to words (perhaps explaining again, inflexibility in speech). Damage to the frontal lobe also resulted in the inability to properly interact with others (i.e., socialization required flexibility), issues with task completion, and difficulty in problem solving (again, something that required – flexibility).

In trying so hard to build references for future use, children such as Zachary wanted things to be “this way or that way”. It appeared as though only “definite extremes” were acceptable.

There were many ways to teach "the in-between" situation to children with autism in order to show them that "references" included more than just the "extreme" scenarios of "this way" or "that way". Once Zachary understood there were “in betweens” and “different ways of doing things”, life became much easier for all of us. Using fractions as I described in my second book under the "Exercises" section was a great place to start.

Recently, I had read a book for Zachary that had well illustrated this issue and the need to teach the “in between”.

This book was The Fire Cat by Esther Averill (ISBN: 0-06-444038-9). In this book, a cat becomes a firehouse cat. Below was the part of the text on page 13 in this wonderful book:

"Pickles, you are not a bad cat. You are not a good cat."

After Zachary read that, he paused. I could see that Zachary was trying to figure out the answer... if not good or bad, what was he? Children with autism knew the “this or that”, but, in this case, the cat was “not bad” and he was “not good”. The book then went on to give the answer:

"You are good and bad. And bad and good. You are a mixed-up cat."

Zachary thought that was absolutely hilarious. What was great here was that this simple children's story provided for the "in between" situation and showed that there was more than just one extreme or the other. In this case, the answer was “both” and the book provided another answer as well… a third answer… “a mixed-up cat”.

I could then add “more answers” for Zachary… saying for example: “some days, he’s a little bit good and very, bad, but on other days, he’s a little bit good, and very, very, very, very bad”… or I could say, “on some days, he’s just a little bit bad, but very, very, very, very, very, very, very good”. Or, I could say, “on some days, he’s not good at all, he’s just, very, very, very, very bad”. This simple example could easily communicate “degrees” of the same thing – those critical “in betweens” that Zachary so needed to understand in order to move away from a world of “this way or that”. Such statement could provide “degrees” or “shades” or “in betweens” for things like “good versus bad” but also “shades” for the same concept, for example, “shades of good or bad”.

In my opinion, it was books and software like this that were needed for children with autism. Books that taught "the in-between" in a fun way... books that made a statement, then provided the opposite... and then, provided the "in-between"... and in my opinion, the more "in-betweens" provided, the better! :o)

There were many ways to show "in-betweens"... you could do it with play dough to show big, bigger, biggest... and go a little more in depths by showing for example, big, a little bigger, a little bigger still, almost the biggest, the biggest. You could really do this with almost anything... spoons, twigs, rocks, etc. and then apply the concept to more abstract things like "emotions" and other aspects of life too where children had more difficulty [more on this later]. Once the concrete was used to teach the concept, it was in my opinion, much easier to teach the same concept in more abstract situations.

During the day, I could easily say to Zachary, “you are a very good boy today”… and then, later expand on that and say, “you are a very, very, very good boy today”. Thus, again, with this simple example, I could reinforce the concepts of “shades of the same thing” and the fact that one did not have to be just “one or the other” – that there were different degrees to a whole lot of things in life! Teaching this concept of “degrees” or “in betweens” – that was one of the very primary keys in my opinion!

Another key in this, however, was that although “inflexibility” appeared to be a sign of frontal lobe damage, “categorization” was not in the frontal lobe, but in the temporal lobe and as such, herein in my opinion, was the potential to unraveling the problem of “inflexibility”.

Everything in life had to be categorized in order to be understood. That included motions, emotions, word associations, etc. Thus, although there appeared to be “inflexibility”, via functions of categorization and the teaching of the “in between” some of that “inflexibility” could certainly be overcome. Thus, teaching the “in between”, in everything – be that emotions, different ways or motions for accomplishing a task, different ways to say the same thing, etc., was absolutely key since each of these “in betweens” could then be categorized in one or many categories. There was simply no denying that categorization functions were critical to overcoming so much in the life of the child with autism!

It was critical to teach these children that there could be “other ways” to come up with the same answer – to teach them that there were often many ways of doing the same thing. For example, it was necessary to teach them that there were many ways to come up with the number 4. The “peg system” I had described in my third book, in actuality, could be applied to so much in the life of the child with autism. “Pegs” provided “first references” that could then be built upon. This concept was so critical that I wanted to provide for parents what I had written on the “peg system approach” in my third book, in order to once again, provide that “common ground” for all parents. For those of you who had read book three, this would be a little repetition and I apologized for that, but, this was also “good review” of an absolutely critical concept. :o)

Start Of Materials From Book 3 On “Peg System”

In so much of what I had come to understand in Zachary, there could be no denying of the critical role of “that label” or “that reference” for him to draw on an the need to show Zachary “more options” or “more ways” to look at things as he formed new memories. The key in my opinion, truly was in making him see that, for example, there was more than one “reference” for adding numbers for example.

I selected these particular examples because they involved short term, long term and working memory. These were but a couple of examples … but, the concept was the same whether one was working with numbers, language or something else. It was also important to keep in mind my belief that the various parts of the brain were perhaps much more inter-related than we may have ever imagined.

Let us take first the simple concept of teaching basic addition. Teaching basic addition obviously involved the working memory, short-term and long-term memory. This also involved functions such as “categorization” and “auditory processing” in the temporal lobe and “higher functioning” in the frontal lobe. Although visual processing was usually involved, clearly, a blind person could learn math too.

If you considered how math was usually taught, it was normally something like this:

1+1 = 2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4, and so on.

In other words, the “peg” or “constant” was the number “1” and what changed were the “other numbers”. It soon became evident to me that in working with Zachary, a child with autism, a child who very much lived “via reference”, there was an inherent problem in this approach. If I taught Zachary math in this way, I was teaching him “a reference” – that 1+1 = 2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4 and so on. Although this was true, I was in actuality, only providing a partial reference for Zachary. Given I knew his was a world of “reference living”, I personally, saw a huge problem with this. I was only providing one of many possibilities for the sum of “2”, or the sum of “3” or the sum of “4” and so on and not showing that – potentially – there were many other ways to come up with the same answer. Indeed, there were many other possibilities… and they increased tremendously the “bigger” the number for the sum.

As such, in teaching Zachary, I decided to “peg” the answer. In other words, I did the following for numbers 1 through 18 (because to do basic math, Zachary had to be able to add at least up to 9+9 to get to the stage of graduating to counting involving units of “ten”). In “pegging” the answer, I now provided for Zachary an understanding that there were “many ways” to get to a specific number, “many options” available for doing the same thing.

For example, to get the number 18, you could do:

|

18 |

+ |

0 |

= |

18 |

|

17 |

+ |

1 |

= |

18 |

|

16 |

+ |

2 |

= |

18 |

|

15 |

+ |

3 |

= |

18 |

|

14 |

+ |

4 |

= |

18 |

|

13 |

+ |

5 |

= |

18 |

|

12 |

+ |

6 |

= |

18 |

|

11 |

+ |

7 |

= |

18 |

|

10 |

+ |

8 |

= |

18 |

|

9 |

+ |

9 |

= |

18 |

|

8 |

+ |

10 |

= |

18 |

|

7 |

+ |

11 |

= |

18 |

|

6 |

+ |

12 |

= |

18 |

|

5 |

+ |

13 |

= |

18 |

|

4 |

+ |

14 |

= |

18 |

|

3 |

+ |

15 |

= |

18 |

|

2 |

+ |

16 |

= |

18 |

|

1 |

+ |

17 |

= |

18 |

|

0 |

+ |

18 |

= |

18 |

For Zachary, this did several things. It showed him first and foremost that there was “more than one way” to do the same thing and it provided for him “the references” he needed to draw from. Granted, you could never provide “all references” in “all situations”, but, by using math, I could provide the “concept” that there were “more possibilities” to something than “just one” – in anything… be that math, language, behaviors, routines, etc. This concept, in my opinion – the concept of showing “more ways”, “more options”, was key in getting children with autism away from their “inflexibility” in so many issues.

But, this simple concept also provided much more for Zachary. It provided for him “the pattern” to see how things worked and hence, the ability to understand how to “break the code”. Zachary easily picked up the concept that on one side, the number went down by one - on the other, it increased by one. Thus, he could actually “see” how this worked.

But, there was still more… for Zachary, this still provided a basic reference… a starting point that he could associate with – a reference easily retrieved and drawn upon or enhanced from there. The obvious “key reference” – though not the only reference for “18” – was the middle point – the fact that 9+9 = 18. For children who loved that concept of “sameness”, this particular reference was key. From this reference point, Zachary could then in his head come to learn to “move up or down” in the chart.

In my opinion, it was also necessary to focus on providing what I came to call “primary pegs” – those basic reference points – the starting points – that could then be used as “key references” in charts such as the “18” chart provided above.

Primary pegs – in basic addition – would include the following:

|

Primary Pegs |

||||

|

0 |

+ |

0 |

= |

0 |

|

1 |

+ |

1 |

= |

2 |

|

2 |

+ |

2 |

= |

4 |

|

3 |

+ |

3 |

= |

6 |

|

4 |

+ |

4 |

= |

8 |

|

5 |

+ |

5 |

= |

10 |

|

6 |

+ |

6 |

= |

12 |

|

7 |

+ |

7 |

= |

14 |

|

8 |

+ |

8 |

= |

16 |

|

9 |

+ |

9 |

= |

18 |

|

10 |

+ |

10 |

= |

20 |

These “same numbers” being “added together”, were in my opinion, key in the life of a child who loved “sameness” and as such, could very much be used to one’s advantage in teaching math based on a “peg system”.

But, there was still more… for Zachary, this also provided that key “categorization” that was so necessary to the understanding of math, language and so many other things in life. A chart such as this provided for “inherently correct” places for things. That was good – initially – but in my opinion – this was but a first step. Eventually, I could easily go to “moving them around” though… thereby, once again, increasing flexibility. For example, although the answer remained the same, I could now change the way “things appeared” in the chart. I could select a “random order” for all the ways to “make 18”, I could show addition involving “even numbers” first, then “odd numbers”. There were truly many things one could do to show that one answer could be achieved in many, many ways. The beauty of this was that it also prepared Zachary for the eventual learning of “negatives” being added into the chart. For example, I could show the fact that [–2+20 = 18] and so on. I could simply add in the “negatives” later on to further build on the concept - in this case - of math – although the application of this same concept could be done for many, many situations relating to many, many other issues.

I also taught Zachary the 1+1 =2, 1+2 = 3, 1+3 = 4 and so on method, but, my primary focus, initially, was on my “peg system” whereby the “peg” was - the answer – not a “variable” within an equation! Providing the “normal method” allowed Zachary to then see how “pegging” different parts of the equation changed the answer! In everything, I tried to provide for Zachary different “ways of looking at things” – “more ways than one” way!

Teaching Zachary math in this way certainly involved his working memory… and it made that “working memory” work in a “flexible way” – because now – he truly saw there could be – more than one way – and I could then apply that concept to much more than “just math”. I could “carry this lesson” to all aspects of life!

As I worked with Zachary, so many things became evident to me. The simple fact was that whether or not a child had autism, all children - all persons - pretty well had the “same brain” – overall. Functions within the brain were all located “in the same place” regardless of whether or not one was “normal” or suffered from autism, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s or any other disorder. A “disorder” in the brain resulted in just that – “dis – order” and the key was in providing once again for something that made sense – in breaking the code to how to once again – provide “order” so that things could once again be understood. As such, these methods could be used for teaching – all persons…

There was no doubt in my mind, that in a child with autism, that “first reference” even if “inaccurate” could be “engrained” in the brain and committed to memory – just as easily as an accurate reference and hence, it was critical to always correct Zachary’s inaccurate guesses or inaccurate utterances during the day… his “inaccurate anything”. An inaccurate point of reference once burned into memory, in these children would be harder to correct at a later date because memories had a way of becoming “more solid” over time – even “inaccurate memories” or “inaccurate labels” (as I discussed in greater detail in my second book – Breaking The Code To Remove The Shackles Of Autism: When The Parts Are Not Understood And The Whole Is Lost!). In my opinion, it would take a great deal more work to “change a bad reference” in Zachary than it would in a “normal person” – and as such, I worked very hard at providing as accurate yet flexible a “first reference” as possible in teaching my son.

End Of Materials From Book 3

Again, a great deal more on this and many other topics was provided in my previous books – books I strongly encouraged all families to read.

Important in all this, however, was the fact that this same concept of “key pegs” could also be applied to language in conjunction with categorization functions [specific examples of that later in this text].

The last function of the temporal lobe I wanted to discuss in this chapter was that of the ability to distinguish between truth and a lie. Although at first it appeared this function was not related to the understanding of language clearly – it was! Repetition allowed the solidification of memories. Memories, once formed and burned into the brain, were not easily “reversed”. Memories, like anything else, could be categorized and that categorization would include a determination of whether or not something was true! The more a person heard something, the more they came to believe that “something” to be true – whether or not, in reality – it was. A person who was told that s/he was “retarded” or “stupid” – if told often enough, would certainly come to believe that. The fact that the understanding of language, auditory processing and memory were all co-located in the temporal lobe along with face/voice recognition (those we believed most were those we knew best) and the ability to distinguish between truth and a lie certainly appeared to make for a nasty situation when it came to this issue.

No man stated it better than he who provided perhaps the best example of the dangers that were simply waiting to be awakened via the manipulation of thoughts and memories as they related to self-worth and the perception of the worth of another human being to society.

“If you tell a lie long enough, loud enough and often enough, the people will believe it.”

Adolf Hitler

Within the functions co-located in the temporal lobe, clearly was the ability to manipulate one’s understanding of the truth via the manipulation of the understanding of language as it related to other functions in the temporal lobe.

Truths, lies, memories, faces, voices, sounds, smells, emotions, and – indeed - all sensory inputs - all of these things had to be categorized – that all key function located in the temporal lobe – a function located in a lobe not associated with “inflexibility” as was the “frontal lobe”. Indeed, categorization functions in the temporal lobe provided, in my opinion, the keys to greater flexibility in these children because categories could be made “flexible” in spite of “inflexibility” resulting from frontal lobe damage. The temporal lobe provided via its categorization functions, a way to increase flexibility in children such as Zachary.

Categorization - a function, that in my opinion, held the keys to further releasing children from the shackles of autism.